Graduating in 2020 from Glasgow School of Art / University of Glasgow with a First in Product Design Engineering, Catriona Brown had long thought that standard issue, plastic tree protectors were an anathema to ‘save our planet, plant a tree’ campaigns. So she set out to design an alternative. Here Catriona introduces Shroom, her tree protector made of mycelium.

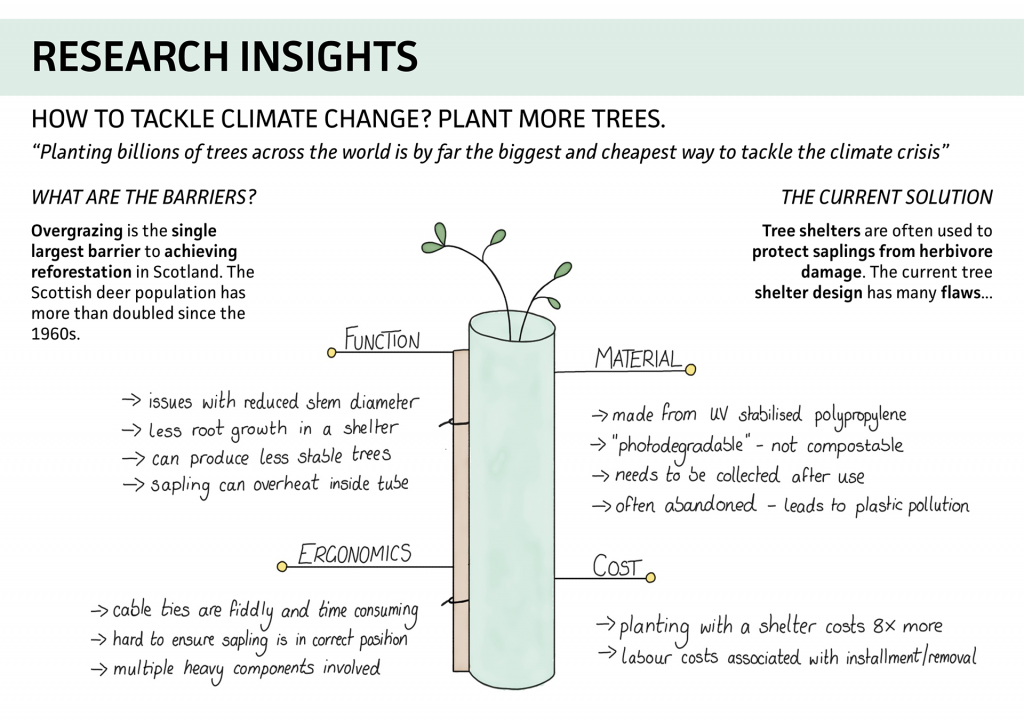

Choosing your final year project can be rather daunting. For me, as someone who is passionate about sustainable design, it was very important to create something that would make a positive impact on our planet. Mass tree planting has been identified as one of the biggest and cheapest ways to tackle the climate crisis. However, this has also exposed serious problems within the tree planting industry, specifically when it comes to the ‘tree shelter’ design.

If you like to spend time outdoors, you will I am sure, be familiar with the light green plastic tubes dotted across the landscape, that are used to protect newly planted trees from nibbling rabbits and deer. If you have taken a closer look, you may also be familiar with the shards of plastic from these shelters or indeed whole tubes that litter the ground, sloughed off by the growing trees. So don’t you think it’s rather perverse that the very protectors of young trees, planted to tackle the climate crisis, are themselves having a negative impact on our environment through plastic pollution? I do.

And it turned out I was not alone in being alarmed by this major flaw in the design of the ubiquitous tree shelter. I was overwhelmed by the passionate responses I received when reaching out to forestry and rewilding organisations. They all shared my frustration and made me realise that here was a problem that could be solved through good design and the use of a biodegradable material.

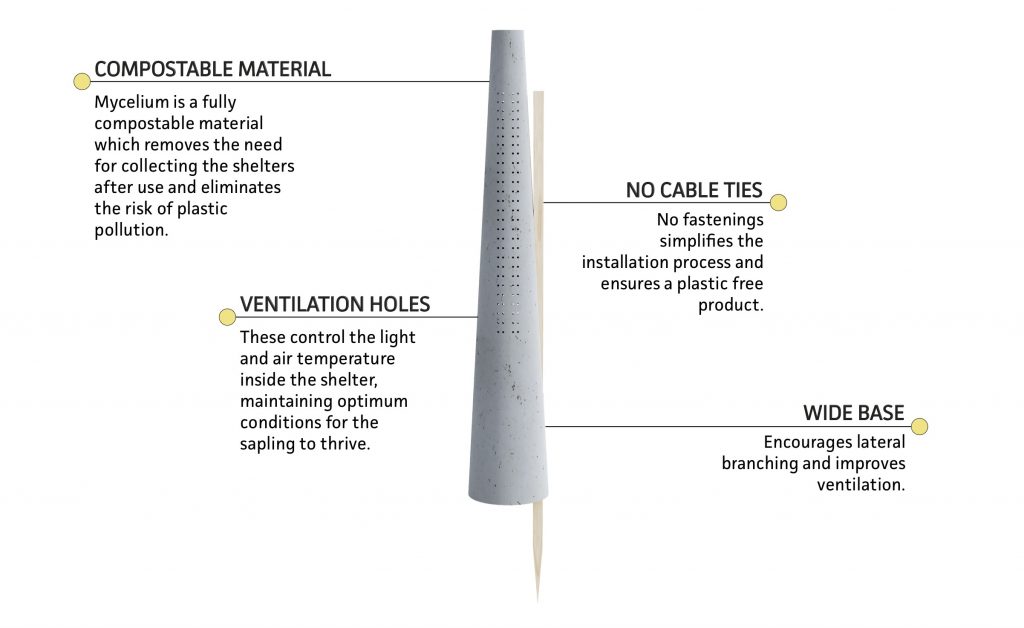

Having a particular interest in materials, I decided to make the tree protector the focus of my final year project at GSA / University of Glasgow. I wanted to work with a material that was both biodegradable and have the necessary life expectancy to protect the sapling from hungry mouths of deer and rabbits. These two contradicting demands made the search for the right material a challenge, yet it led me to the most fascinating of materials – mycelium.

So, what is mycelium? Mycelium is made from the root-like fibres of fungi that grow beneath the ground. These fibres branch out and intertwine, connecting plants and trees to create a network through which nutrients can be shared. These threads of mycelium when interwoven are uniquely strong and can be harnessed to create a solid material. To do this the mycelium is combined with a substrate, such as dry plant matter, which is the most abundantly available raw material on earth. This can be sourced from local agricultural waste. Once the mycelium and substate are combined it is put into a mould and left out of direct sunlight to ‘grow’ for 5 days. During this time, the mycelium ‘eats’ the substrate, to form a natural glue, which in turn forms a solid material in the shape of the mould. What’s more, growing mycelium has a very low carbon footprint, as the mycelium itself is doing all the work, rather than machinery that demands ‘power’. In addition to this, when producing one tonne of mycelium, two tonnes of CO2 are captured from the atmosphere.

As you can imagine, I was soon in complete awe of this material and determined to use it to create a new kind of tree shelter. In order to access its feasibility, I needed to get in touch with mycelium experts. This led to Ecovative, a biotech company based in New York, who are market leaders in producing mycelium products. They also have great online resources including a Youtube channel which demonstrates how to ‘grow’ mycelium.

Closer to home, I found a company in the Netherlands called Grown.bio who use Ecovative’s technology. Grown.bio were able to provide insights into how mycelium material works and how effective it would be if used to make tree protectors. There is ample evidence of mycelium’s ability to fully decompose, so the main challenge was to see if it could protect a vulnerable young tree from predators for as long as necessary before decomposing.

Mycelium is already used in a variety of applications including lighting, furniture and packaging. What really caught my eye was its use in architecture. This proved mycelium could be both a durable and weatherproof material. Grown.bio directed me to a project called The Growing Pavilion. Launched at last year’s Dutch Design Week in Eindhoven and conceived and designed by Pascal Leboucq and Lucas De Man, of the Amsterdam-based initiative New Heroes, this circular pavilion was constructed of mycelium panels that were protected by a bio-based coating. This coating extended the lifetime of the mycelium to around 15 years. Proof of a longer lifespan was the evidence I had been looking for. I was now able to take mycelium forward to the next stage of development.

This is where the real fun began. Grown.bio sell ‘Grow-it-Yourself’ kits which was ideal as it meant I could actually get my hands on this amazing material. The kit consisted of a bag of mycelium hemp substrate which is pressed into a mould of your choice. I started with sandwiching the mycelium between bowls and baking trays before creating my own custom moulds with cardboard, sealed with sellotape. The mycelium will ‘grow’ into any mould cavity so you can be really experimental.

After forming a better understanding of the material’s properties and capabilities, I started to draw up designs for the actual tree shelter. From conversations with tree planters and tree experts as well as doing some tree planting myself, it became clear that the instalment process for the shelters could be drastically improved. I was determined to remove the need for cable ties which are used to secure the stake to the current plastic tree shelters. These are not only fiddly and time consuming to attach but also created an additional plastic waste component. After a long process of sketching and prototyping, I landed upon the conical form and named the shelter ‘Shroom’. This new design allowed the shelter to be slotted straight onto the stake with no cable ties.

At this point things took an unexpected turn when lockdown was announced. Plans to carry out site tests were delayed, and I could no longer access the workshop, so making a full-scale prototype was ruled out. However, I was determined to work around these obstacles and managed to make some homemade prototypes which I trialled in my parents’ garden in Helensburgh on the west coast of Scotland.

Designing a new product normally takes years but my Shroom prototype was developed in just under 7 months so it was bound to present a challenge in how to most effectively produce and take to market. I have to admit I am naïve about what is involved in taking a product to a point of production and sale. I’m not going to lie, after submitting my project I had kind of accepted that Shroom would remain a concept rather move into a reality. So I was completely taken aback by how many people contacted me having viewed Shroom as part of my online degree show. It was so lovely to see people were genuinely interested and saw real potential in my design. Yet in all honesty, I also quickly started to feel very out of my depth.

Words like ‘patenting’ and ‘funding’ were thrown around and I had no idea where to start. It was exciting though. I started to see how my project could be taken further. I am aware my concept isn’t perfect and there is still further development and testing to be carried out before I would consider it a ‘final’ design. The design process is all about going through many iterations. As I start the next chapter of my design journey, I am looking forward to forming collaborations and partnerships with fellow designers and organisations. Working alongside others, who share the same passion for sustainable design as I do, could be the key to taking this project from a concept to a viable product.