The academic and Lector in Design at the Royal Academy of Art, in The Hague, Alice Twemlow discusses trash, deep time and the Scottish Enlightenment geologist, James Hutton.

Hear our recent conversation – Alice Twemlow discussing Design in Postnormal Times with Chris Breward.

What’s the view from your window?

It’s the sounds, heightened by the surrounding quiet, that I am most tuned to: the creaking lurch of the trampoline in the yard next door; outtakes of piano practice from an open window; blackbirds in the cherry tree, a distant dog’s bark.

You studied in the UK and the USA but since 2015 you have worked in the Netherlands, first teaching at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Did you find the Dutch design landscape very different from the British one?

Prior to moving to the Netherlands, I spent 17 years in New York where, amongst other roles, I was co-founder and director of an MA in Design Research, Writing and Criticism at the School of Visual Arts. Concurrently, I completed a PhD in Design History at the Royal College of Art. My dissertation became Sifting the Trash: A History of Design Criticism, published by MIT Press in 2017.

MIT Press 2017

In the Netherlands, I was first a tutor at the Vrije University MA in Design Cultures and tutor then head the Masters program in Design Curating & Writing at Design Academy Eindhoven. I was surprised to find such a pronounced separation between “academic” university education and “vocational” design education. On the one hand you have university courses, where design is studied at a clinical remove from the sites of making. And on the other, art and design academies where research cultures are only emergent. Was there a hybrid space in-between, where research into urgent social issues could take place using the tools, methods and sensibilities of design practice? Well, yes, it turns out — in the form of a lectorate, a construction unique to the Netherlands, created to bridge this divide between academia and practice and to bring research into the heart of art and design schools.

In 2017 I was appointed Design Lector at Royal Academy of Art, The Hague and Associate Professor in Artistic Research in the Academy for Creative and Performing Arts at Leiden University. Here I am busy on design-focused research culture within KABK and Leiden University, at the end of each year we organize a public symposium, Fault Lines.

So yes, the Dutch design landscape is very different. Here there is less commercial and corporate work, and more government-derived arts funding. Design, or at least the kinds I tend to be in contact with, leans toward, and sometimes merges indistinguishably with, art practice in ways that I found disorientating at first, but now am quite relaxed about!

Poster designed by Vera van de Seyp

In your writings you quote the French philosopher Bruno Latour: “Between modernising and ecologising we have to choose,” which sums up the central dilemma of 21st century design. How has this dilemma shaped your thinking?

In my doctoral research I used the conception of sifting – the design critic as a sifter of trash to explore various critical engagements with design in the US and the UK since the 1950s. Bluntly speaking, you can see the critic as a gatekeeper of the landfill, consigning some products to its depths, salvaging others. I was studying the use of trash as metaphor. But I became more interested in the trash itself. I realised that we needed a closer critique of what happens when a designed entity becomes trash – the social behaviours, politics, infrastructures, mechanisms, and economies that shape and gather around its disposal.

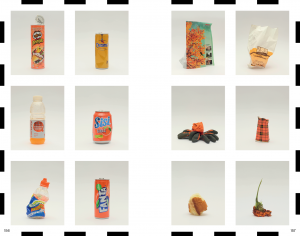

Too often our engagement with design focuses on only one moment in a product’s lifecycle — the moment when it is brand new, box-fresh, and suspended in the perpetual present tense. We need to address when its usefulness is over, when it gets thrown away. For, as we know, there is no “away”.

It becomes part of the 1.3 billion tons of municipal solid waste we produce globally per year. And then it becomes part of our planet, a distinctive stratal component, a key geological indicator of the Anthropocene.

We needed to look beyond design, to other disciplines to provide models. In fact, trash becomes a fulcrum for many disciplines. I explored branches of archaeology, garbology, discard studies, eco-criticism, geophilosophy, and geobiology, among others. Geobiologists stress the importance of discussing different timescales beyond the merely human one, such as evolutionary, cosmic and geological time or ‘deep time’ as it is known.

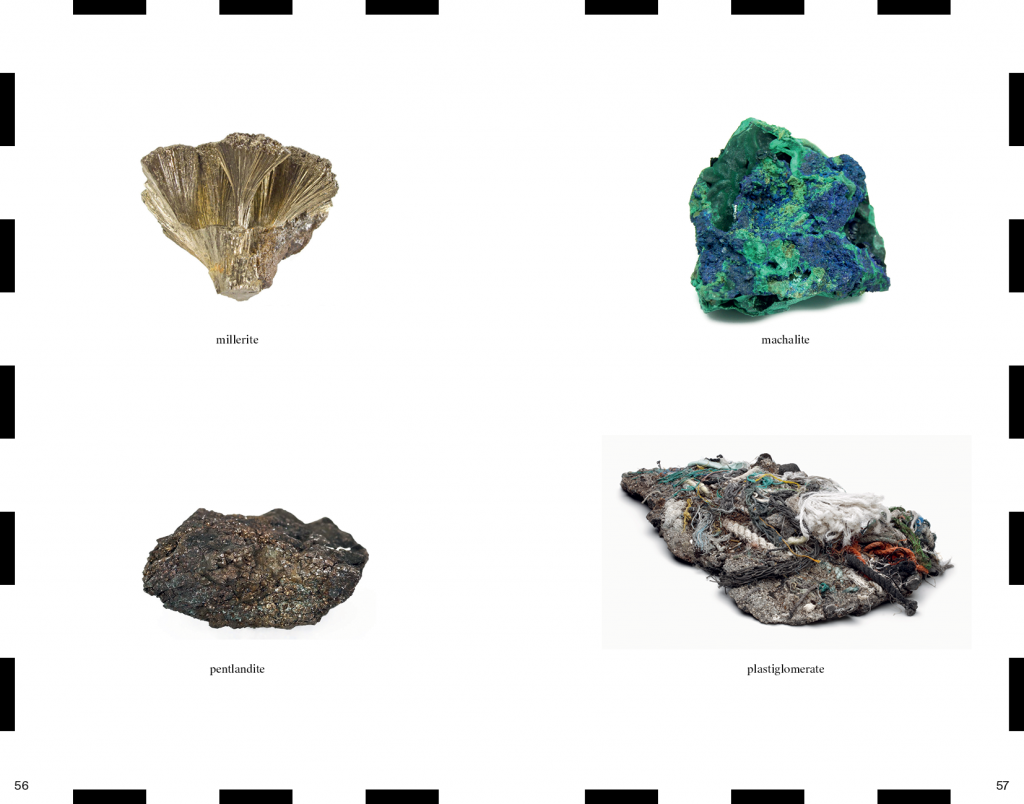

I named my lectorate at KABK ‘Design and the Deep Future’ to allow for exploration of plastiglomerates; space junk; and digital detritus, in courses like ‘Future Fossils: A Design Archaeology of the Here and Now’ and ‘Speaking Across Deep Time: Designing Markers for Nuclear Waste’.

I often come back to Latour, because for whatever designers produce—however well-intentioned, thoughtful, or alluring— it simply is another piece of stuff (digital or physical) on a planet already choking on stuff.

One way that Latour’s directive has influenced my thinking is in my research into various responses to this impasse: adaptive re-use and repair; the custodial use of things, places and experiences, rather than ownership; the use of “just-in-time” and small batch production methods; and the design of emotionally durable products. I’m also seeing an interest in products and communications that are designed specifically to remove and efface themselves after use, to dematerialize, to be disassembled and re-used, or even to remove other designed things. Self-destruct mechanisms are found on devices and systems where malfunction could endanger large numbers of people, so why are they not included on more designed products? How might subtraction, the impulse toward nothingness, and genetically modified lifecycles, contribute meaningfully to the manmade landscape? While self-destruction is more usually considered as pathology—the symptom of an abnormal mental condition—some product designers are curious about the creative potential of artfully choreographed self-destruction, decomposition, and de-activation and about the new values and insights the notion of productive nihilism might bring to the design conversation.

You reference the great Scottish geologist and Enlightenment figure, James Hutton in your work. What do you find so engaging about his writings on geological time?

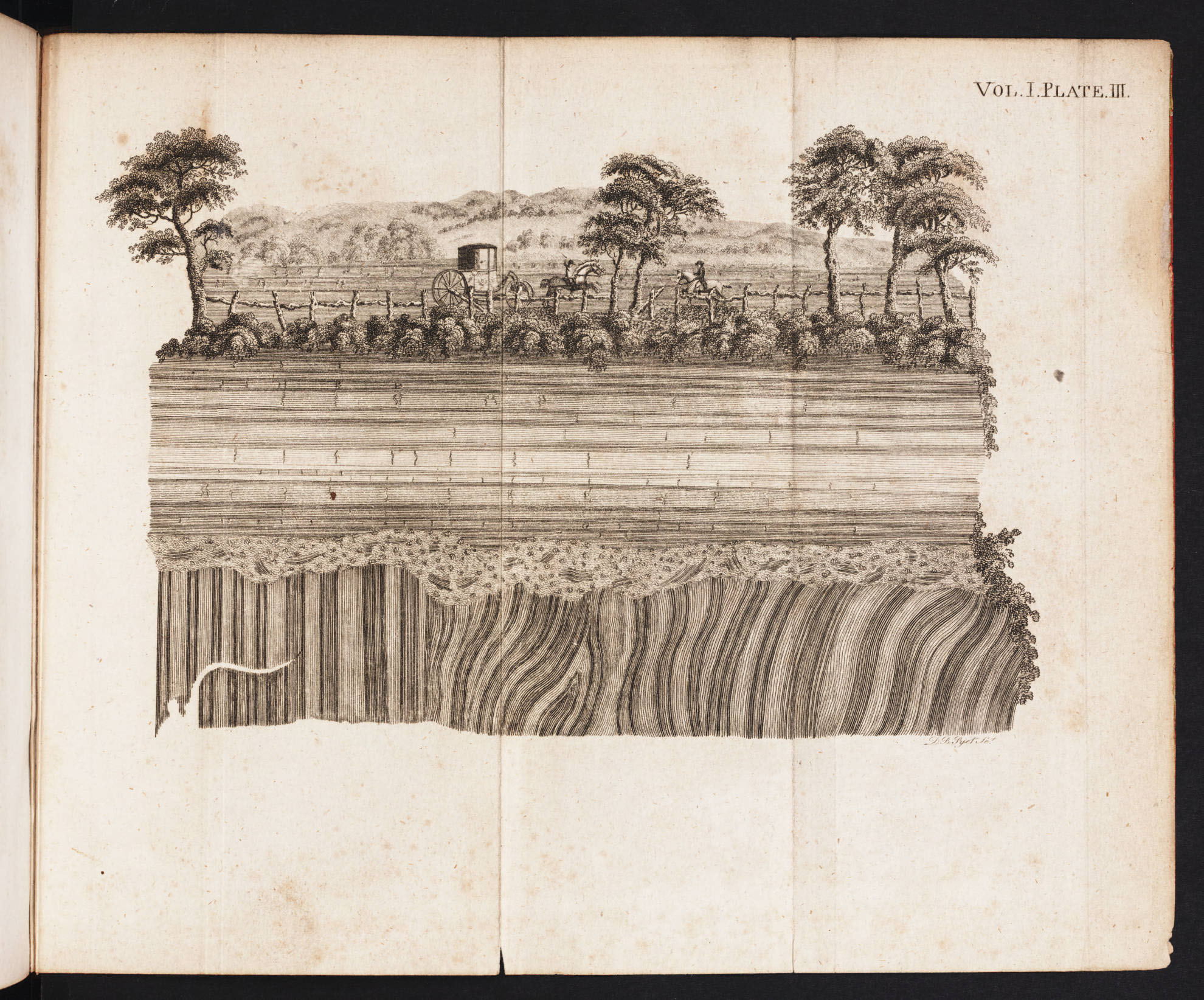

The geological concept of “deep time” was coined by the American writer, John McPhee in 1980 but refers to one developed by James Hutton (born Edinburgh 1726 – 1797), to explain the endless cyclical process of rocks forming under the sea, being uplifted and tilted, then eroded to form new strata under the sea. I must admit that I have only read extracts of Theory of the Earth, published in 1795 by The Royal Society of Edinburgh, accompanied by engravings of incredible drawings by John Clerk of Eldin, but I was struck by the way Hutton described the temporality of this earth metamorphosis as one in which “we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.”

This magnitude of scale that Hutton refers to surely helps us get design in perspective. Especially so, when you consider our current geological era, the Anthropocene. This a unique phase of human history, in which the slow-motion processes of earth’s systems and the ephemeral products of our disposable product culture are understood as interconnected. We design products that are used fleetingly but end up with lifecycles much longer than our own and become part of the planetary record.

What projects are currently working on?

During this stay-at-home period, I would have to qualify the verb “work” with attempting-to work. There’s the underlying buzz of anxiety and guilty helplessness, the overlying drone of my husband’s daily Zoom work marathons, and my bat-like ability to echolocate from behind two closed doors when my 11-year old son drifts away from his online schooling and into the yawning abyss of YouTube.

More than this, I realise how much my work needs people in the flesh to make real sense. So much of what I do is about choreographing social situations, whether for teaching or research, and while you’d think this could be replicated online; I can officially report that it cannot. My teaching and research project supervision does continue in its new strangulated formats; but not for a moment longer than it has to.

I’m writing for London Review of Books, a reappraisal of Dunne & Raby’s seminal text Design Noir for a book about Critical Making and some fiction. I have also completed an essay on Formafantasma’s practice for Disegno. The main project I’m developing however is KABK Research Practices. Our first edition focuses on walking as a research method. Last week we uploaded a video of an interview I did with public space and landscape designers Krijn Christiaansen and Cathelijne Montens of KCCM who teach at KABK. What I’m learning is how walking is used as a method in different disciplines like geography and how it differs in art and design.

Roel Backaert, camera and editing by Yannick van de Graaf

We are living life very differently at the moment, and perhaps thinking about the ‘emotional durability’ of the things we buy and have around us? Do you believe this pandemic will make us reassess wisely the way we live our lives?

Unfortunately, as climate scientists have reported, even if we continue like this, with carbon emissions so dramatically reduced, we still won’t be able to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5 C by 2050 that we are striving for. But, yes, I do think consumer practices may well be fundamentally changed both as a result of individuals’ positive experiences of the simple life, and by the reshaped economic landscape we are about to emerge into.

You are spending more time working from home at the moment, is there a particular object you are enjoying?

Living in Amsterdam my bicycle is usually a means to an end, a preferred mode of transport, but in the last few weeks it has taken on a new significance. It gives me perspective-gaining journeys along the industrial wharf-edged IJ to the north and the reed-fringed Amstel to the south.

Do you have favourite lockdown book?

The book I’m reading with page-turning pleasure is The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins by the anthropologist Anna Tsing. The book describes the globalized commodity chains that exist around matsutake mushrooms that only grow in human-disturbed forests. Contaminated diversity (the key to collaborative survival), Tsing tells us, is recalcitrant to the kind of summing up that has become the hallmark of modern knowledge. What she proposes are more attuned modes of listening, noticing and then telling what she calls “a rush of troubled stories.”

Listen to Design in Postnormal Times, our conversation with Alice Twemlow. Visit Alice’s website. For more on James Hutton & John Clerk of Eldin head to National Library of Scotland and the Linda Hall Library in the USA.