The Italian-born, Amsterdam-based duo, Andrea Trimachi and Simone Farresin are Formafantasma. Here they talk about their lives in design and their 2020 exhibition, Cambio at Serpentine Galleries, London

Formafantasma – it’s a brilliant name for your collaborative practice. When did you first begin working together and what inspired the name?

We first met while studying for our Bachelors in Florence in the early 2000s. We went on to decide to apply to the Masters programme at Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands. We did so as a duo, with one portfolio for the two of us. As to the name formafantasma, we had it in mind from the start, it roughly translates as ‘ghost shape’. It suggests that our work is not driven by formal research but more by a conceptual approach.

Experimentation is integral to your work, which you describe as a form of learning. Can you describe this approach?

Our practice is research based but also intuitive, at its best it is political with attention to context and the historical background of the subject of investigation. We would sum it as research-based, contextual, historical, political, intuitive.

Your exhibition Cambio at the Serpentine Galleries, London focuses on the life and after-life of trees, on the vital importance of wood as a commodity, fuel, a raw material and of course its ability to absorb C02. What led you to explore the world through this one material?

When we spoke to Hans-Ulrich Obrist, [artistic director at Serpentine] more than a year ago about the possibility of doing a show, he was interested in exploring the possibility of an exhibition that displayed a designer’s thinking rather than just their products. He was curious about the collaborative nature of our work, so the invitation was perfect because we have always wanted to focus on the research process in an exhibition.

We decided to focus on timber because it offered enormous possibilities, in as much as it is a non-extractive material, compared to for instance, minerals. Trees are a living species that contribute to the world in many more ways than just providing wood. Our aim in the first place was to better understand the level of complexity we are all working and living in. While taking such an expansive subject such as wood, risks generalisation, we firmly believe in the necessity to read and understand design within its larger context, one that includes extraction, refinement, production, distribution and afterlife of things and materials.

At the same time we want to offer clear reflections and design questions: ‘How can the practices of observation and care toward living plants – tuning into their life, features, behaviour and necessities – shed light on our own ecological and entangled lives?’ ‘What can we learn about climate change by analysing the anatomical features of trees?’ ‘How would wood production change if we take more fully into consideration their ability to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere?’

As designers we ask how we can make more informed choices when selecting a wood-based material over another, beyond its aesthetic and functional properties? And perhaps most importantly, how can the imagination and ‘elastic’ approach of design be helpful in translating today’s emerging environmental awareness and scientific knowledge into informed, collaborative responses?

These are strange and challenging times but have you found lockdown has given you the opportunity to pause for thought, consider new ideas and possibilities?

Yes absolutely. We are obviously scared like everyone else about the impact of Covid 19, nevertheless the imposed lockdown is making us reflect on our way of working. We will do our best not to go back to the same life we had before in regards, for instance, travelling. We are also focusing more on ideas we think are meaningful and discarding the ones that are not relevant.

For too long, design has based its development on essentially one big narrative: to attain human well-being and to satisfy human desire. This indulgence of human aspirations has debased design and narrowed down its scope of intervention, and where it has looked beyond the production of objects, it engages only with the transformation of half-finished materials into desirable products. Design needs to question the infrastructure that facilitates this process.

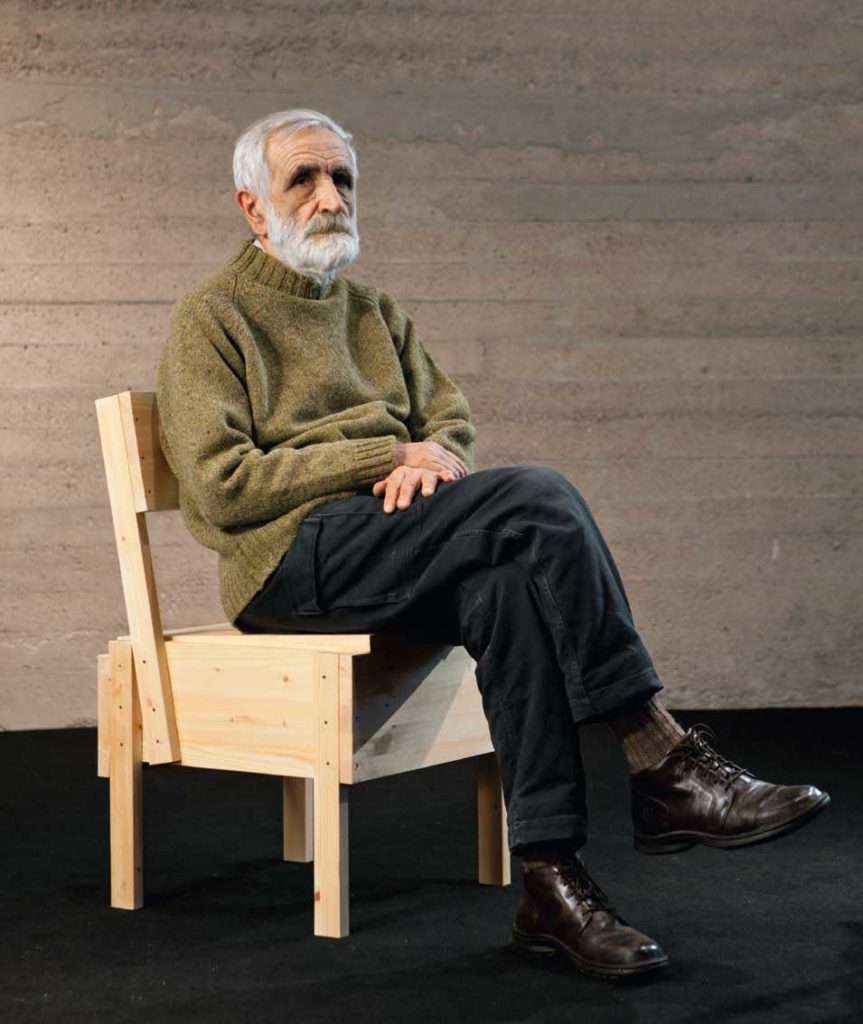

Is there a designer or a particular object or landscape that inspires you?

We always love the work of the Italian artist and furniture designer, Enzo Mari. We also find the work of the contemporary philosopher and writer Emanuele Coccia endlessly relevant and inspiring.

What’s the view from your window?

A wall covered in ivy.

Do you have a favourite lockdown recipe, book or piece of music?

Theorem, the 1968 film by Pasolini and the song Citta’ vuota by the Italian singer Mina and Chestnut soup – boil the chestnuts, then peel and boil again, they will naturally disintegrate and then add a few leaves of bay, salt and pepper and olive oil. Delicious!

Installation images – Cambio, Serpentine Galleries London. Photography Gregorio Gonella, George Darrell & Simona Pavana.

Download the Serpentine Galleries Cambio exhibition publication.