Jude Barber is an architect based in Glasgow. She is director of Collective Architecture with offices in Glasgow & Edinburgh. She recently announced her bid to become president of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

You are currently working from home, what’s the view from you window?

I live in a tenement in Pollokshields on Glasgow’s Southside. I work from a high-ceilinged room with tall vertical windows. It overlooks the street, my neighbours’ doors and windows and all the everyday activity that comes with it.

Did anything in particular prompt you to train as an architect?

I’ve always loved drawing and making. As a teenager I thought of jobs I might do where I’d get the chance to do that. I was also interested in social history and psychology, so I think that, combined with drawing, led me into architecture. I was also lucky to get work experience placements within architect’s offices in my final years at school (in both Aberdeen and Forres) and enjoyed the range of activities the architects seemed to be doing. I particularly liked the site visits to so many interesting places I’d never been to before. It’s one of the things I still love about my work.

You joined Collective Architecture in 2005. Does the practice have a particular ethos?

The practice was founded in 1999 as Chris Stewart Architects by Chris Stewart on principles of sustainability and participation. We became Collective Architecture in 2007 as a 100% employee owned studio.

Collective Architecture is more than a name for us; it reflects our inclusive, flat operating structure and our approach to design. We all share equal and financial ownership of the company, are actively encouraged to develop our own skills and innovate. We ensure our work is guided by principles of trust, openness and inclusivity.

Glengarnock, North Ayrshire

Over the past 20 years the work and structure of the practice has evolved to affect the way we design and collaborate. We continually oscillate between individual ideas and collective action. This process mirrors our approach towards wider participation, where we work closely with clients, collaborators and communities. Ultimately, we want to create quality buildings and places that are fit for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century and beyond.

Collective’s recent projects include Paisley Learning and Cultural Hub, Granton Waterfront in Edinburgh, Garnock Community & Visitors Hub in Ayrshire and social housing at Leith Fort. Is this engagement with both smaller projects and bigger masterplans & issues of sustainability, social space and well-being vital to the practice?

Yes, we design a wide range of projects together. Everything from small exhibitions to large scale housing projects. As an architect you can apply your skills and process to any brief.

Working at differing scales is something I relish. I think it keeps my mind nimble and skills fluid. For example, last year I was co-working on Edinburgh’s expansive and ambitious Granton Waterfront Strategy whilst co-designing our tiny Voices of Experience ‘Mementoes’ exhibition in the Lighthouse Glasgow. I loved the fact that one minute I’d be thinking about how to position the height of an archive box on in the gallery and the next I’d be discussing climate resilient landforms for a coastal park with engineers and landscape architects. Currently, working at spatial extremes allows me to best test ideas and interrogate what we can do as architects and who we do it for.

You recently announced your candidacy for the presidency of RIBA, the Royal Institute of British Architects. What prompted this?

No one thing prompted me to do this. And it‘s quite hard to explain why I felt so compelled to stand at this particular time. But ultimately I’m motivated by the urgent need to collectively address the climate emergency, to tackle extreme social and spatial inequalities (reinforced by the recent pandemic) and to embed equality diversity and inclusivity into everything we do – in practice, policy, procurement and education. As architects, we need to apply our skills for the needs of the 21st century and create a landscape within which we can be more agile, resilient, and ingenious to do that.

You are a key member of New Chapter and Voices of Experience, would you say campaigning is integral to the way you work?

Possibly – but it’s not intentional! Both initiatives you mention were instigated, and motivated, by a desire to address some of the barriers or gaps in the landscape of making architecture. You can have all the talent in the world – and the best intentions – but if the landscape within which you work doesn’t support you – or excludes others – it’s like banging your head against a brick wall all the time. So, if you have the agency and support, you should try to change the landscape. I’ve also found that there’s a certain type of creativity and agility in activism that seems to feed into my work and projects.

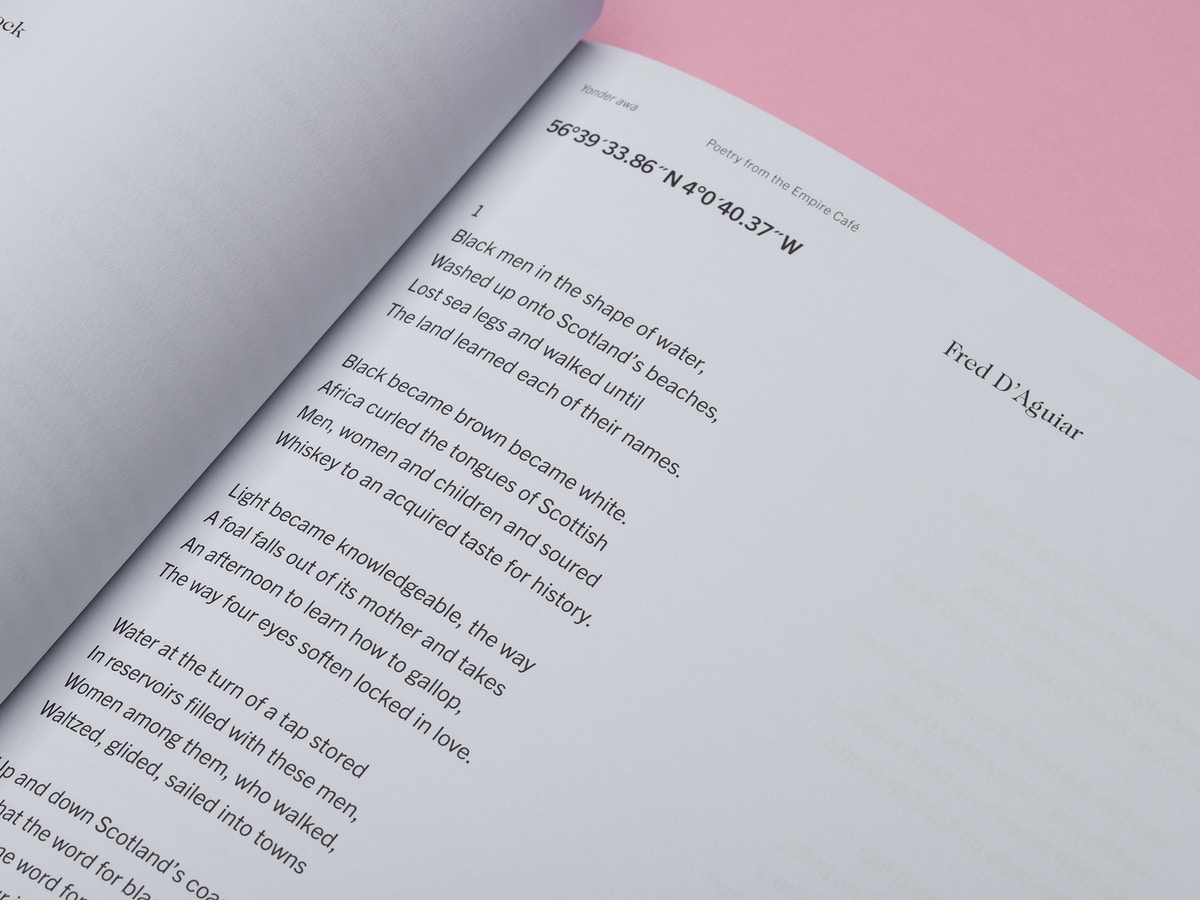

In 2014 with the writer Louise Welsh, you founded Empire Café to explore Scotland’s role in the North Atlantic slave trade. Do you have plans to revive this project?

We were both fortunate to work with – and learn from – so many wonderful people in the process, including Graham Campbell, Dr Stephen Mullen, Sir Geoffrey Palmer, Graham Fagen, Leonie Bell and Jean Cameron. We don’t have plans to revive the project in the way we did in 2014, but Louise and myself are developing some other plans together. In 2019 Glasgow launched its study into historical links with transatlantic slavery led by the fabulous Dr Stephen Mullen. In the same year, Glasgow University publicly noted its historical links with the transatlantic slave trade and associated financial benefits and has established a restorative justice scheme. CRER (Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights) have been calling for a Museum to Black History for years. Just this month, there were calls via a competition idea from Gavin Fraser, to establish a Museum of Slavery in Alexander Greek Thomson Egyptian Halls on Jamaica Street.

Design Graphical House Glasgow

This period of confinement has prompted a rethink of design & architecture & the vital importance of the domestic space – the provision of gardens, adaptable spaces for home-working and schooling; the front door step and stoop for conversation and engagement with neighbours and ‘street life’. Has the pandemic ‘refreshed’ your thinking.

Oh yes. I really hope this period of confinement has highlighted the need for careful, site specific architecture for everyone. Space standards, daylighting, thresholds and spaces between building have been thrown into sharp focus at the moment. Particularly with our unpredictable Scottish weather conditions. And the gap between those that have quality living environments in their neighbourhoods and those that don’t has never been clearer. We need homes that capture the light, provide space and flexibility for all types of activity to take place, bay windows to lean out of, doorways within which to shelter and gardens to enjoy. And collectively we need more local parks we can safely walk to; arcades we can shop under and accessible public buildings within which we can gather. Plus –we also need to campaign and fight for public toilets!

Lockdown as alerted many of us to consider more carefully about what is ‘near to hand’ or ‘under-foot’. Is there anything in particular that has surprised you?

Absolutely. We are all acutely aware of what we have, or don’t have, on our doorsteps at the moment. The one thing that’s surprised me is how strongly I feel about cars dominating space – everywhere. I keep looking out our window or walking to the shops and imagining our neighbourhood with no coveted, metal boxes sitting everywhere. I think generations to come will look back at this and consider it ridiculous.

What’s your favourite building in the world, in Scotland?

That’s a hard question! I don’t have one favourite building – but there are many that have stayed with me and influenced my thinking. We’ve been making regular trips to Finland with our family in recent years. We’ve visited – and returned to – a host of buildings by Alvar Aalto’s studio and those have made a huge impression. Most notably Sayntsalo Town Hall with its rich spatial arrangement and gorgeous application of materials. In the process I’ve learned more about Aino Aalto and her work and influence in the studio (which I didn’t learn at Architecture School). Also, when I visited the Alhambra in Granada about 10 years ago, I marvelled at its detail, history and integration with the landscape. At the time I remember being sorry not to have been educated about it – and Moorish architecture – as a younger person. Since then I’ve been trying to open myself up to projects and architecture from around the world.

Where would you head to if you could?

I’d head up to the back shore in Findhorn, Morayshire. It’s a coastal village in the north east of Scotland where my parents live and where I went to school as a teenager. I don’t think I appreciated how special it was until I had left. Although I’m an adopted Glaswegian I still hanker to get back there, see my family, walk the lanes and think on the beach.

Favourite book or food? How do you relax?

I find it quite hard to relax as there are always so many things to do. I enjoy getting ‘lost’ in making something – but I’m finding that hard to focus on any one thing at the moment. I’m fortunate to live with my partner and daughter who both love to laugh, cook and talk. I think I’m at my most relaxed when we all get the chance take time over a meal and debate the world in the company of close friends and family.