DES invited architect Paul Stallan, founder of the Glasgow architectural practice Stallan-Brand, to share his thoughts on how to ensure a building is architecture.

“When approaching a new architectural design project, I conceptualise the challenge not as a single large initiative to be solved by one mode of thinking but one that requires multiple strategies and inspiration to resolve. Here I outline six architectural descriptions of buildings which have addressed the critical themes that architectural production wrestles with.”

Dream

A building without a dream is a building . . . a building with a dream is architecture.

If architecture is to be different from mere building it needs ‘art’ – it needs a dream, a conceptual ambition. I have a simple equation to explain; ‘Building + Art = Architecture’. An architecture which I enjoyed where the dream was large is the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh designed by the Spanish architect, Enric Miralles and supported by his partner Benedetta Tagliabue, an extraordinary architect in her own right. I was privileged to work on the project at its inception and track Enric’s unique process. The dream was huge, layered and nuanced, infused with Enric’s deeply humanist politics with a love of landscape and literature. A generous, disorganised genius. His architecture flawed, unresolved and wonderful. Enric seemed to design both backwards and forwards compared to how architects are traditionally taught. He designed chairs, windows, even a pattern for the carpet, unconcerned that the building plan and organisation was at large.

“A giant Scots Broth of a process, deeply frustrating to all in the world of project management, but great fun watching the fireworks and confusion as a consequence of his collagist process“

His architectural language so dense with abstract association can be overwhelming. Take his iconic pop-out windows that array across a massive broken slab elevation, like a hundred little tree houses, each with a small stair and bookcase, a seat and an alternate vantage point. But what of the dream, what do all these idiosyncratic moves mean? His dream was to create a building that was part of the landscape that was intensely complex, one with no front or back or seeming direction, a deconstruction to be inhabited by many different voices. Enric’s aim was to create a building with as many corners, nooks and niches as he could with extraneous circulation. Why? Because he wanted to encourage ‘skullduggery’, spaces for continuous plotting and negotiation a building porous with conspiracy, a necessary function for democratic vibration.

Place

To provide cultural meaning to our architecture

There are some works of architecture that are inseparable from their place of production. This appreciation has in recent years taken on much greater agency with the chronic failure of the modern zeitgeist no longer seen as a solution to absolve the horrors of two world wars, address poverty and liberate us, but coming to represent only economic incentive. Local variation has new priority to put the ‘where in the where’, with new concrete stories. The tour de force of place specificity in recent Scottish architecture is the Museum of Scotland on Edinburgh’s Chamber Street designed by Benson & Forsyth. A great pudding of a building soaked in symbolism. Where our Parliament celebrates our future in our past without sentiment and expanding into the landscape, the Museum does the reverse. It places our past in the now within a massive stone keep. The metaphors that the architect Gordon Benson mined, span the millennia, from ancient Shetland brochs, to moats & drawbridges, arrow slots & ramparts, through to modern infusions of Mackintosh, Le Corbusier & Basil Spence. A layer cake of architectural history is cast in a concrete corset. Bound into this architecture treasure vaults, trophy rooms and secret passages with artefacts waiting to be re-discovered, all of this complexity curated with specific reference to its immediate context, cognisant of key views and vistas yet bullying into its historic setting.

Site

To resolve issues of aspect, orientation, respond to views and vistas, negotiate topography, encourage a microclimate and much more.

There are great works of architecture that as well as being ambitious, visionary and the outcome of inspired cultural production are also celebratory in terms of their unique siting. When an architecture is synergistic with its natural or built environment, you are encouraged to appreciate that environment more fully. A square of grass on a gentle glacial tilt within the tidy Helensburgh grid-iron is such a site. Elevated to a complete work of art, this is Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Hill House. Put aside the joy of the Mackintosh vernacular and examine Hill House forensically. Using diagram eyes you discover the compositional secrets of the house. The form, spatial distribution, narrative curation, landscape structure, every architectural design move underpinned by decisions that literally kiss the context. Take the buildings plan and consider the placement of rooms along its central axis. Rooms are arranged either with a south aspect or a north aspect juxtaposed with dark paneling or white plaster, animated masterfully by the play of light and the passage of the sun through the sky. If you rotated the building 180 degrees it would be like giving the architectural aesthetic an anaesthetic, immediately obscuring its meaning and rendering it mute. The architecture goes further to command its gentle sloping plot to frame a south facing lawn where walls extend to the boundaries of the site, no opportunity missed, all rituals considered.

Space

To order rooms and spatial relationships within architecture to support our daily rituals.

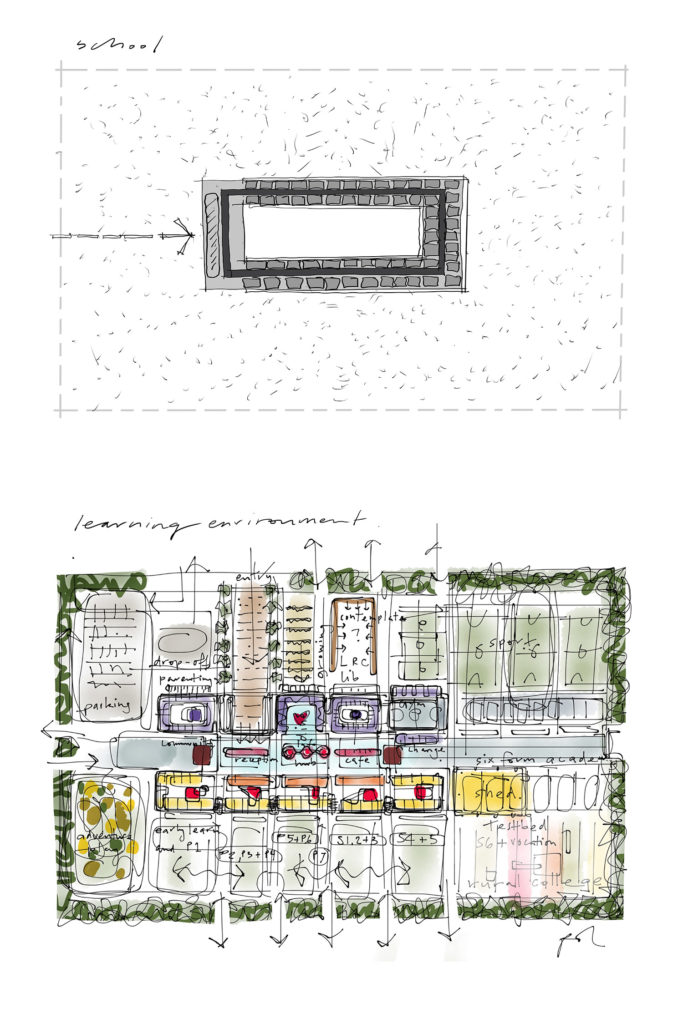

Architectural space frames our experiences as building users. As a practice fully involved in the design of new types of learning environments this is a subject we take very seriously. In this fourth design observation I describe how and why as a practice we are addressing the urgent need to ‘re-choreograph’ the spaces in existing and new school designs. Stallan-Brand with Scottish Borders Council is changing the school model to address the opportunity that Scotlands Curriculum for Excellence provides. The driving force behind the design is students taking ownership over their teaching space and encouraged to curate their own learning. Classrooms become studios and the school plan becomes porous learning landscape. Critically our design avoids the typical routine of high school where students are dislodged between lessons hourly to traipse between generic classrooms to any of sixteen subjects. In our new Jedburgh Intergenerational Academy, the pupils experience learning in larger year group studios with the teachers moving between, different to the departmental model where the provision of small enclosed rooms that are the domain of the teaching staff and limited to an individual subject. Jedburgh is the first school in Scotland to completely address the spatial demands of the 3-18 Curriculum referencing Scandinavian education models that place an emphasis on wellbeing, recognising that people learn in very different ways. There is an urgency in transitioning towards this type of environment towards less anxious space to address a mental health crisis that is affecting our young people. Our practice believe that the nurture agenda central to primary education needs to extend through the whole learner journey encouraged by environments that are less institutional.

Machines & Systems

To imaginatively consider a building’s systems, skeleton, essential organs and circulation.

Structure in buildings like structure in nature is the skeleton that gives a form its shape. It is fundamental that architects understand the principles of structural design to resolve an architecture with integrity and economy. The building superstructure has then additional layers of building systems including ancillary features like lifts, stairs, ramps, cupboards, toilets and kitchens. A skilful architect will thoroughly exploit the qualities of these layers within a building understanding that each has a unique opportunity to add richness and additional meaning.

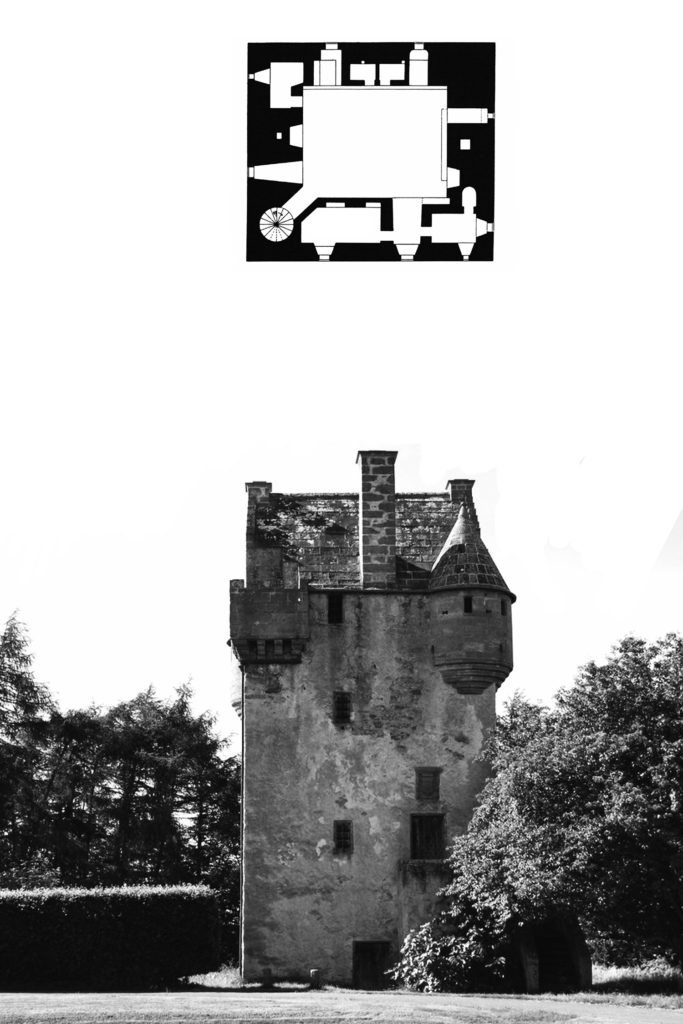

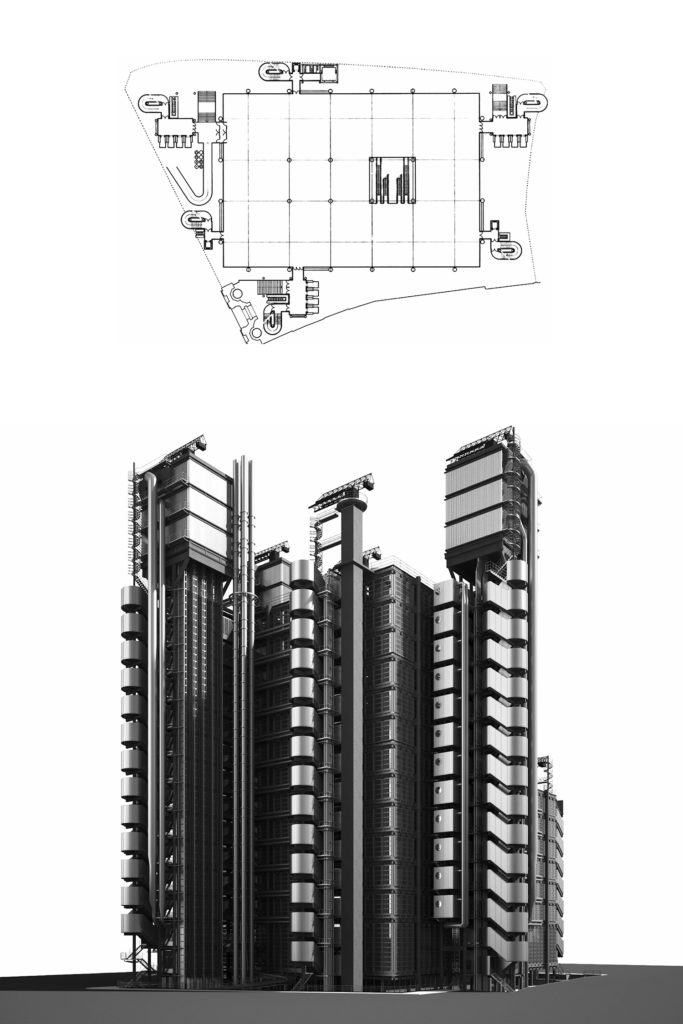

To reinforce the design opportunities that the study of systems provides, compare and contrast the plan form of a traditional Scottish Tower House and the plan of Richard Rogers Lloyds Bank in the City of London. Essentially they have the same plan diagram, a single space surrounded by ancillary spaces and necessary ‘machinery’. The Tower House is of course a monolithic construction of stone where the parts needed to make the house work are embedded into the depth of the wall thickness, whereas with Lloyds building, they are quite literally ‘plugged-on’. Lloyd’s like the Pompidou in Paris is an extreme example of architecture celebrating its systematic construction, everything from structure to building services legible.

Design

A journey of intuitive self expression and rational thinking.

Architecture and artistic self-expression are not easy bedfellows. Architecture, different from art, implores public scrutiny and processes that can dilute spirited work and result in conceptual fatigue. To counter such malaise requires a reasoned architecture language that people will be excited by, that they understand and that means something. At a personal level, I have tried to develop a means of making and a language of architecture that people will engage with. To do this I have been compelled to understand the criticality of those dreams, places, sites, spaces and systems in architecture as I have described. I make designs with reference to these priorities which are critical to architectural production. I have been exploring these themes through an ‘architectural painting and collage practice’ for the last 25 years. They are not representations of any particular landscape or building, rather an attempt to unpack muscle memory and explore form and narrative.

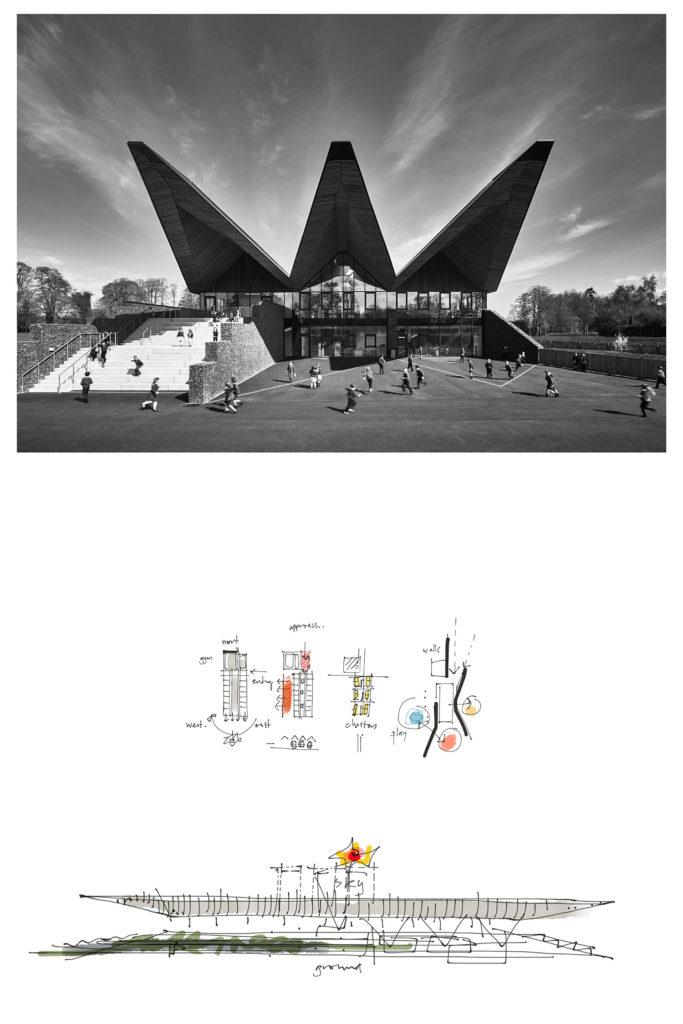

Architectural education when it focuses on form-making tends to be formulaic and prescriptive compared to the anarchy of experimental aesthetics. The latter is however much more rewarding – and has kept me excited. A project that tips the balance of intuition over rational thinking is our new Broomlands primary school in Kelso. It evidences an expressiveness, the benefits of which are hard to quantify, other than to reference the disproportionate love that the children and community have given it. The buildings form a compound abstraction of local vernacular and spaceships.

Paul Stallan is design principal of Stallan-Brand, a studio that he established with fellow architect Alistair Brand in 2012. Paul has designed award-winning education, urban regeneration and cultural projects both locally and internationally including the 2014 Commonwealth Games Village and being a member of the team who delivered the new Scottish Parliament. Paul pursues an independent art practice borne out of his architectural process.