Artist & writer Kate Morgan explores & exposes the twists & turns of sock making from the mighty MUJI to a modest Czech knitting grandmother.

1

In 2006, in search of the perfect sock, MUJI discovered Czech Grandma Ružena’s knitted right angle socks – and they fitted perfectly. MUJI wanted more people to experience this comfort, but until then, socks were created at a 120 angle, development began and, with that, the world changed … by 30 degrees. MUJI had to reinvent the entire manufacturing process to mechanise the hand knitting technique. The sock has been so popular that since 2010, it’s the only kind of sock that MUJI makes.[i]

[i] MUJI UK : [accessed 3/09/20, text no longer on site as of 7/12/20]

Browsing the MUJI (UK) website on the third of September, I came across these lines, heading the page for women’s socks. I know this because I have a record of it; I sent them directly to a friend, copying and pasting them in digital space, in enthusiasm. On the twenty third of September, I bought six pairs, which were delivered on the thirtieth to my front door by someone called Kieran, at some time between 13:06 and 14:06. Later, on the twelfth of October, the socks still very much alight in my mind, I took a screenshot of the webpage. Sometime between then and the next time I looked, which must have been in November, MUJI altered the site. This passage, so compelling and conflicting to me, is no longer available on MUJI UK. It is this erasure that is the focus of this essay.

2

Across MUJI’s global websites, different iterations of the text exist, though there is little further information to make clearer the terms and circumstances of MUJI’s interaction with Ruzena, the maker of the original socks on which MUJI’s right-angle socks are based. A few articles written by external journalists parrot and rephrase the same original text. I tried myself to get them to budge, to give me more information than those trite sentences on the header of their website. I got an email back that, though it was kind, felt in texture like a brick wall.

Weeks later, I read a 7000 word tome of an interview between Masaaki Kanai, the head of Ryohin Keikaku (MUJI’s parent company), and another man in a suit, Kazufumi Nagai, president of another design company. I learn that MUJI was founded in 1980 by Seiji Tstutsumi, in opposition to the mass consumer habits of the time, with two distinct tenets: that of mujirushi, or ‘no brand,’ and that of ryohin, ‘the value of good items.’ Kanai says that at MUJI they don’t advertise the specific names of an object’s designers, and that:

. . . the designers took a birds-eye view back to the so-called anonymous designs from before the advent of the consumption society. Whether you were talking jeans or baseballs, or even axes for cutting down trees, no one knew the name of the person who designed these items. The axe, for example, evolved into an efficient tool over the course of hundreds of years.[i]

[i] Ryohin Keikaku : [5/12/20]

Is this approach the one they used with Ruzena? Is even having her first name as credit seen as too much within MUJI’s ethics system? Or, do they see her as part of that distant past, where objects developed over hundreds of years, and so see her acts, her life, her distinct lack of anonymity (they know her full name, even if we aren’t allowed to), at the end of that line as invalid? In giving us her name only in half, and in their shedding of even that forename from the company sites over time, MUJI makes steps to push her back, push her acts back in to the distant past, back into nameless craft work. Is the effect of this erosion that MUJI takes all the credit? Is this what happens when one looks at both ‘the past’ and the craft traditions of those from other cultures as a thing to be mined? — as in the ‘hunting expeditions into bodegas, factories, street markets and artisan workshops around the world, led by [MUJI’s] design guru Naoto Fukasawa.’[i]

[i] Quora Article [1/12/20]

3

It’s a Tuesday night and I am balling up socks, standing in the back of the kitchen, with the lamp standing beside me. We are comparing the black and the black now, and I am a batch in. You’ve got to push your outstretched hand into them…turn them from being inside out, and that gives you an idea of the feel of the fabric, so you can find a nice match. Some have a bit more give, some are stiffer, you can tell that some are a higher quality cotton. In a true pair, each sock slackens in the same places.

4

I found the information I’d been looking for, or at least some of it.

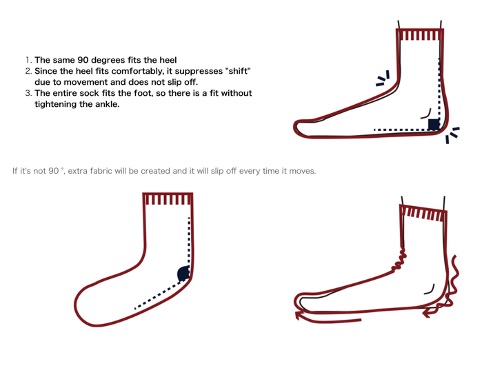

I can’t remember how I navigated to this starting point, but begin here, (translate it if you can’t read the Japanese), and open the hyperlink at the bottom to find ‘Encounter with Czech grandma.’ [i] It is in this place only that an image of Ruzena is stored within the MUJI multiverse. Just above this, and click the link to ‘Why MUJI socks are right-angled’. After some annotated diagrams, there is a subtle hyperlink ‘continued here’ which opens to another website: mujinet.

Through mujinet, you can get to mujilab, where consumers are able to submit their feedback, all responded to by someone from the ‘development team’ with comments to the effect of we’ll get right on it. A few clicks distant from here, I find my way to the ideapark, a conceptual ‘park ‘within mujilab, where I finally get the goods: pages and pages of product development, which I read, all in no doubt fumbled google translation. One report from an employee tracks two years spent trying to make MUJI’s right angle sock not slip down the ankle.[ii] There are candid photos of men in an office on exercise bikes, cycling, wearing the socks, and photos of some kind of fabric distressing, hammering machine, (incredible) and accompanying descriptive photos that show how much this machine can degrade the sock’s heel in a certain amount of time, and I live for this stuff.

I slip, fast, back into fully standing by this, becoming entangled, letting my eyes be closed by the reams of photos of factories, of suits in boardrooms drawing on whiteboards, of close ups of the grain of the knit. Into fanaticism. Despite all this, I wake in the early hours and remember that, for all of the pleasantness of that report on ankle slippage, there is not any word I can find of those primary visits to the Czech Republic — there is a distinct arms-length-ness to that side of the story, the sock’s origins. I’m reading just these dandy glory days of mujilab’s forays into being more generous with information. I am sitting alone with an absurdist story, which reads like it was written in a fever dream, about how they are trying to standardise size, so that all their clothes fit all people, and it feels as if nobody but me has read this offering since it was first published on the site in 2011.[i] There is a disjunct between MUJI’s tight advertising and packaging output, their business-minded output (like the interview with Kanai), and things like this, which feel as though they are past (forgotten) errors of judgement – they are so expansive in the information they give.

I wonder at how all this action, all this positive action, translates to the MUJI I have witnessed – that dimly lit shop, now closed, in Whiteley’s in London’s Bayswater, now knocked down, a straight line away from home, where once upon a time I saw the actor Alan Rickman looking at their children’s toys, and now can’t remember if that was a lie, fabricated or embellished to make a good story.

The no-brand-ness became the brand, the familiar red letters, the brown craft paper board, the plastic cellophane, objects of fetishisation. It was the first place I saw kanji characters, plotted out on stickers like postage stamps on each item.

5

I am stressed about the fact that Ruzena might or might not have invented this method – these ‘perpendicular socks,’ and that I am acting her advocate, (does she want me to?) whatever the truth might be. From the photo of her socks, they seem quite complex. MUJI’s is quite different; a lot has changed, or maybe it’s more about what you can hide when something is machine-made, the knitting that much finer. Kate Atherley, who heralds custom-made socks on her knitting blog and in her books, talks about the flap-and-gusset mode of heel construction, which looks more like what Ruzena did.[i] This shows precedent, or at least that other people were making socks something like hers: that she didn’t reinvent the wheel. We are firmly in the area of a craft tradition, years and years, hands and hands, and not that of the fluke inventor, which MUJI presents Ruzena as in their material.

Atherley also talks a lot about something called negative ease, where you knit a sock to smaller dimensions by about 10% to those of your feet. She says a sock must stretch to not bunch, to encompass your foot nicely. I think about the person, unnamed, who spent the two years developing an anti-slipping sock. All the work they did, experiment-like, in the lab, and how craft tradition in its totality seemed to elude them.

In the development of their right-angled sock, has MUJI reinvented the wheel, though? Great developments have been made: the whole mechanisation process had to change, all that sock-slip work was done. I am at odds. It is hard to think it through. They are grappling with difficult things: the body is a difficult thing to contain.

6

In 2006, in search of the perfect sock, MUJI discovered Czech Grandma Ruzena’s knitted right angle socks – and they fitted perfectly.

Those lines become a mantra, I can recite them aloud to myself, type them out without referring back. Brittle, alight, ruffled, doubting, engaged: made all those things by these words, themselves banal on the face of it. I am trying to outline how my relationship to them is a complicated one, why the socks won’t go away. They reverberate. The toe, that most distant extremity, is what first comes to be cold upon unfolding the body from under covers. The socks first clothe, then. Especially in the winter months, they are the first in a series of items to warm open skin.

MUJI wanted more people to experience this comfort, but until then, socks were created at a 120 angle, development began and, with that, the world changed … by 30 degrees.

It is dark outside, again, and I am again balling up socks. Trying to think if this 30 extra degrees is really doing anything for me. At intervals across the last few weeks, I look down from the computer, or from a plate of food, or from the view of my hands stirring at the hob, to check on my socked feet. Are they assuming the 90 degree posture or the 120 degree? At this moment, sat at a desk, one leg is folded over the other, which pins its foot at a sure 90 degree angle to the floor. The foot which hangs in the air, suspended by crossed legs, adopts instead the almost pointed 120 degree posture. My feet occupy both positions, so how to pick one?

MUJI had to reinvent the entire manufacturing process to mechanise the hand knitting technique.

This interests me; the wackiness of reinventing whole systems of production. How that seems anti-capital, or how maybe that is the urge of capital, to have to do something so grand to win a consumer over. The sock has been so popular that since 2010, it’s the only kind of sock that MUJI makes. When we pick a brand and then pick an item from it again, we show trust. I am satisfied with the giving over; with being a consumer who looks for good design, whatever that means. But — there is this other part of me, who isn’t the best consumer they are looking for, (‘We’re looking for the best consumers to offer them a more fulfilled lifestyle.’) I am sometimes a person for whom buying isn’t purely about the value and the quality, where a brand having an identity itself holds value. It is for this version of me, where the values of mujirushi and ryohin are less important, that the complication arises. A brand can be transformational; an object can house elements of one’s identity, be the container and conduit of it. In opposition to the clean utility purported by MUJI, and something more like the neon-lit Japan of the 1980s that MUJI was borne out of a distaste for. But – I sometimes need to inhabit that kind of Blade Runner-aesthetic.

The socks don’t work, for one. Maybe they have been tested, pulled on and off over and over, for an office context, in some regular business shoe, or worn with one of their no-brand cotton trainers, but they haven’t been tested for me. It is raining one afternoon, and I pull and zip on my boots (my 90s, white, patent, boots) over my socks (my striped MUJI 90 degree socks). The boots sit at a cross section of the hyper-practical (they are all I have that will withstand this rain, and because they sit on a flat platform, I can walk through water), and the highly impractical (the footprint being also an inch, more, wider than my foot across the whole circumference. My ankles flex to the sides whenever I wear them, testing being broken. I have tried to go up muddy gradients in the park in them; it doesn’t work). I go outside, walk out, and within a few steps the MUJI 90 degree sock, that world changer, lauded by the company as a revelation, inside a boot, has slipped down below and past my ankle.

It suffices in a platonic way, its systems remain slick and functioning in the mind’s eye, and to an extent here in the home, maybe in the executive lounge, were it to come to that, but not outside of those spaces, in the nit and the grit.

7

Today, browsing MUJI Australia’s Facebook page, I found an accent on Ruzena’s name. Everywhere across MUJI her name is spelled without one. This makes it: Ružena. So: you pronounce her name, the single first name that we have for her (which means rose in English), differently to the way I have had it fixated in my mind all this time. It is more of a vibration, the z changes from being sharp and at the front of your mouth, to something that sounds like the ‘s’ in measure. The word is more inside the mouth than on the tip of the tongue. Ružena.

8

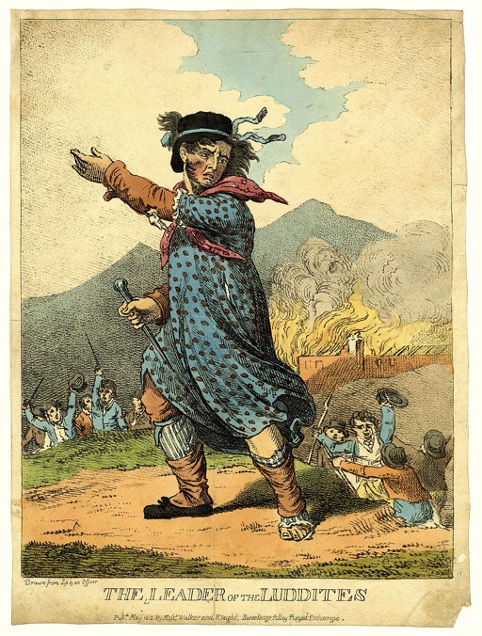

There came to being in 1779 a fictional hero, called sometimes Ned Ludd, and other times General Ned Ludd, and even other times King Ludd, who lived in Sherwood Forest. Depictions show him, ragged, holey socks un-darned, buildings in flames behind him: a fictional hero of the working classes.[i]

Ludditism arose in earnest in Nottinghamshire in 1811, when mechanised stocking knitting machines were purposefully broken by textile workers, and handloom weavers burned factory machinery and whole mills. Such acts spread across the UK. Followers of Ludd, Luddites, protested the introduction of power looms for making their socks and stockings, as well as the wage reductions and mass unemployment which were a result of such mechanisation.

This story, and Ružena’s and MUJI’s, is in essence one of mechanisation – what good it brings and what bad it brings, and how people speak of it.

It is about the point where the forehead of the industrial butts right up against that of the crafting body. Both stories bear different marks of wear from the same source: a body pushing outwards, (toes, ankles, heels, whole people), defying that which attempts to enclose them (a sock, a machine, a structure). A toe through a hole in a toe of a sock.

9

In the woods, in lore, nothing is new — even the object or fruit summoned out of thin air by a figure in disguise does not possess that sheen of the new. It is novel, yes, but it is known; familiar. Perhaps this is because we speak in, and exchange only, platonic items in such worlds: the apple is always a gleaming red one, rounder and more red than you could know, and with the perfect stem coming up from its centre.

I think I am thinking about stories — how often when we tell them we don’t know that we are. And how a story is not ever something without its own specific colouring. And how, the stories we tell are often stories we are telling ourselves, moreso than to an audience. How, in a story when you hold up a sock it’s just so — it isn’t a sock that will go on a real foot. MUJI is trying for something that doesn’t exist; for an ideal that is in image only, an ideal that can’t take a human foot. I am thinking about how we try to support objects with stories, how in that passage (In 2006, in search of…) MUJI tells themselves a story, one they are trying to convince themselves of.

How a story, itself an erosion and a building on the truth, can be eroded, can be neutered. How this information about Ružena is very hard to find, and how now on none of MUJI’s 35 global sites does this information hold a clear place. How it used to, and how it no longer does. How this slippage made no sound?

1. Email Response from MUJI. Screenshot, own.

2. MUJI Right Angled Sock [7/12/20]

3. Abrasion Tester [7/12/20]

4. Screenshot, own, from MUJI’s UK website [accessed 3/09/20, no longer available 7/12/20]

5. Sock Meeting [7/12/20]

6. Explanatory Diagrams [7/12/20]

7. Ružena [7/12/20]

8. Ružena’s sock [7/12/20]

9. The Leader of the Luddites [18/03/21]

Read Kate’s earlier essay commissioned by DES – WOOF.

Kate Morgan is a writer/artist based in Glasgow, currently studying Creative Writing at the Royal College of Art, London. Morgan is interested in things we do with our hands; in the words that we use; in the labour of manual craft work and its effects; in technologies old and new, and in what’s for dinner. Recent works include Pointing (2020), a collection of prose poems, and Screw Head (upcoming, 2021, with David Solomon) a self-published chapbook in collaboration with her father, of writing and drawings about screws. She exhibited A Bench for ‘The Universal Holding Device’ at Design Exhibition Scotland, 2019. @kaetmrgn